Coding · ·

SQLite and SQL queries

There are various different relational database engines that use SQL (structured query language), one of which is SQLite which we'll be using. Other popular SQL database engines include MySQL, PostgreSQL, MariaDB, Oracle SQL and MS SQL server.

You can use SQLite directly from the command line, or from server-side code eg with Bun. You can't use it from the client-side (web browsers). We'll be using Bun's built-in SQL library for SQLite.

While you could use SQLite for your websites, changes you make to the database won't persist the next time you git push. For full persistence, a later guide will show you how to switch to a cloud-hosted PostgreSQL database instead, through Bun's same SQL library.

1. Quick start

You'll be creating several files. You should create a new folder to put them in, probably not inside your website's repo.

Start with a .js file eg sql-queries.js with the following:

import { sql } from 'bun'

process.env.DATABASE_URL = ':memory:'

console.table(await sql`SELECT 'hello world' AS message`)

Run it and you should see:

┌───┬─────────────┐

│ │ message │

├───┼─────────────┤

│ 0 │ hello world │

└───┴─────────────┘

- line 1 imports the

sqlfunction from Bun's built-in SQL library - line 2 sets an environment variable called

DATABASE_URLto use SQLite's in-memory database- alternatively, you could put

DATABASE_URL=":memory:"in a.envfile in the same folder

- alternatively, you could put

- line 3 runs an SQL query on that (empty) database

I've used console.table() instead of console.log() for prettier output, but if we console.log'd instead we'd see that the result of running the query is an array of results.

Notice the strange syntax in await sql`SELECT 'hello world' AS message` (no (brackets) but backticks instead)? This is correct, and uses something in JavaScript called "tagged template literals". sql is a function, which is taking one argument which is SELECT 'hello world' AS message. But the backticks around that argument cause it to be treated in a special way, which alllows the function to do funky things with it (such as preventing SQL injection here). We have to await the result, as the function returns a promise (to avoid blocking the thread).

2. Loading the sample database and using basic SQL SELECT queries

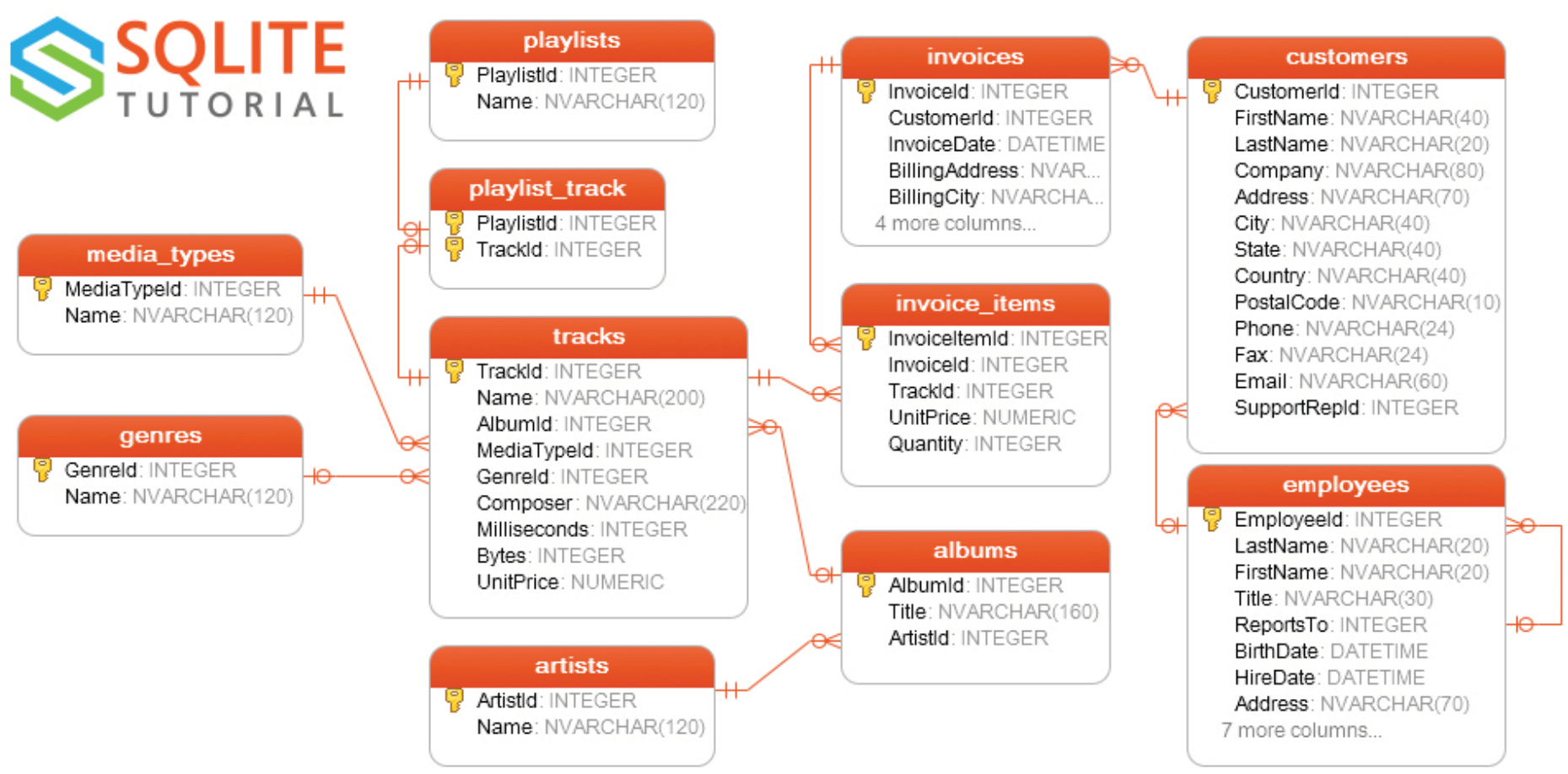

We're going to use a sample database (from SQLite Tutorial) which we first need to import from an SQL 'dump'. A dump is a file containing the schema/setup of a database's tables and/or the data to go in it, made up of SQL statements which can be run to create the tables and/or populate them with the data in your database. Here's the structure of the database we'll be using - you may want to open it in a different tab to refer back to at various times:

Start by copying tutorial.sql into the folder you're currently in. I suggest you open it up in VSCode and read through some of the lines as well.

Put the below code in a JavaScript file, and run it with Bun:

import { sql } from 'bun'

process.env.DATABASE_URL = ':memory:'

// start with our tutorial database

let tutorial = await Bun.file('./tutorial.sql').text()

for (let line of tutorial.split(/;\r?\n/g)) {

if (line) await sql.unsafe(line)

}

// you'll generally only be editing the query below

console.table(await sql`SELECT * FROM employees`)

When you run the program, you should see a table of output showing the details of 8 employees from the sample database.

Your program read the tutorial.sql file and ran the ~15,000 SQL queries inside to populate a database in memory. Then finally, it ran your query on that database.

Here are some more queries to try - just edit the last line of your JavaScript file to try each one:

SELECT * FROM employees- shows all data in the employees table, but a bit ugly as lots of columnsPRAGMA table_info(employees)- shows what columns are in the employees table; let's just pick a fewSELECT firstname, lastname, phone FROM employees- only show some columns/fieldsSELECT name FROM sqlite_schema WHERE type ='table'- find out what other tables there areSELECT * FROM tracks- woah... 3,503 records isn't very useful to displaySELECT COUNT(*) FROM tracks- so we might usually want to check this before getting everythingSELECT * FROM tracks LIMIT 10- now just the first 10 rowsSELECT * FROM tracks LIMIT 20, 5- show 5 rows, but skip the first 20SELECT trackid, name, composer FROM tracks LIMIT 20, 5- the same, but only some columnsSELECT name, composer, unitprice FROM tracks WHERE composer = "U2"- shows all songs composed by U2SELECT name, composer, unitprice FROM tracks WHERE composer = "u2"- shows nothing because the search term is case-sensitiveSELECT name, composer, unitprice FROM tracks WHERE composer = "U2" ORDER BY name- sortedSELECT name, composer, unitprice FROM tracks WHERE composer = "U2" ORDER BY name DESC- and reversed ('desc'ending order)SELECT name, composer, unitprice FROM tracks WHERE composer = "U2" ORDER BY name DESC LIMIT 5- just the first 5 of those

Queries can get very long (I can remember writing 50+ line queries for a company I used to run). It's fine to split them over multiple lines. Here's the last one split over a few lines, formatted nicely in JavaScript:

console.table(await sql`

SELECT name, composer, unitprice

FROM tracks

WHERE composer = "U2"

ORDER BY name DESC

LIMIT 5

`)

... the order is important. SELECT ... FROM ... WHERE ... ORDER BY ... LIMIT. It will also be very picky about things like rogue or missing commas. Can you spot the mistake below?

console.table(await sql`

SELECT name, composer, unitprice,

FROM tracks

WHERE composer = "U2"

ORDER BY name DESC

LIMIT 5

`)

Of course, you can do anything with the query result, not just log it to a table:

let tracks = await sql`

SELECT name, composer, unitprice

FROM tracks

WHERE composer = "U2"

ORDER BY name DESC

LIMIT 5

`

for (let track of tracks) {

console.log(`${track.Composer} made a song called "${track.Name}" which costs $${track.UnitPrice}`)

}

... notice the column names need to match the case-sensitivity that you'll see in the table headings (and this database uses PascalCase not camelCase).

Have a good browse through the database by exploring some of the commands and queries you've just learnt above. You can also browse and run queries on the same sample database online (click "...or download & try this sample file" then drag that file back onto the page).

3. Persisting the database

Remember how I said in a previous lesson that databases have to be persistent? At the moment, our JavaScript is starting from a fresh in-memory-only database each time it's run, then reads in and runs a bunch of SQL queries from tutorial.sql to populate our database. There's no persistence there at all - if we ran a query to modify the database, those changes are lost when our program exits.

Create a new file called reset.js with this, and run it with Bun:

import { sql } from 'bun'

let file = 'tutorial.db'

process.env.DATABASE_URL = `sqlite://${file}`

await Bun.write(file, '') // clear any existing db

// start with our tutorial database

let tutorial = await Bun.file('./tutorial.sql').text()

for (let line of tutorial.split(/;\r?\n/g)) {

if (line) await sql.unsafe(line)

}

... if you ls in your folder after running the script, you'll see you now have both tutorial.sql and a new file tutorial.db - this is the persistent database you'll be using from now on. If you ever mess up the database, start fresh by running this script again.

Your main file where you're trying out queries should now be shortened by removing the bit where you're populating from tutorial.sql, and it also needs to know which file the persistent database is stored in. This is what you want in it now:

import { sql } from 'bun'

// connect to our persistent database tutorial.db

process.env.DATABASE_URL = `sqlite://tutorial.db`

// you'll be editing the line below

console.table(await sql`SELECT 1`)

You'll probably find it runs significantly faster too, as it's just running your one query on the persisted database, rather than having to run thousands of queries first to populate the database.

4a. Optional: Using SQLite without Bun

This step is optional partly as I now encourage Windows users to use PowerShell instead of WSL. If using WSL (or macOS or Linux), go ahead and try it out.

You don't need to be inside Bun to use SQLite. You can access it from most server-side programming languages, and it also has its own CLI tool.

Install SQLite from within WSL (no need to install on macOS as it's already installed!) with sudo apt install sqlite3, then run it with sqlite3. You will see the sqlite> prompt, can exit with .exit at any time (try it now then run sqlite3 again) and can see help with .help.

Forgotten your WSL password?! In PowerShell or cmd run

ubuntu config --default-user rootthen open WSL and typepasswd [username]egpasswd jake(yes, passwd not password) and choose a new password. Then back in PowerShell or cmd runubuntu config --default-user [username]egubuntu config --default-user jakethen you're good to go - just open WSL again.

Within sqlite3 you can run any SQL query, but put a ; at the end of it to run it, eg SELECT 1;.

If you want to use the tutorial.db file you created in the same folder you're currently in, open sqlite with:

sqlite3 tutorial.db

As well as normal SQL queries, there are various commands you can run that start with . such as .help:

.tables- shows the names of all tables.schema- shows details of each table.schema artists- shows details of the artists table.header on- show field names at the top of each column.mode column- use tabs instead of | characters to separate columns.exit- to leave the program

4b. Interogating table names and details

This assumes you skipped the optional

4aabove, as this section provides the same functionality without using thesqlite3CLI program.

Sometimes you want to find out what tables are currently in your database and what fields are in which table. These SQL queries can help:

SELECT name FROM sqlite_schema WHERE type = 'table'shows the names of all tablesSELECT sql FROM sqlite_schema WHERE sql IS NOT NULLshows details of all tablesPRAGMA table_info(artists)shows details of the artists tableSELECT sql FROM sqlite_schema WHERE name = 'artists'shows even more details of the artists table

5. More complex SELECTs

You can do a lot more with a SELECT query. Here are some examples to try:

SELECT * FROM invoices LIMIT 10SELECT DISTINCT(billingcountry) FROM invoices ORDER BY billingcountry- that's our country listSELECT * FROM invoices WHERE billingcountry = 'United Kingdom' ORDER BY total DESC- remember case sensitive search termSELECT * FROM invoices WHERE billingcountry = 'United Kingdom' AND total > 10 ORDER BY total DESC- an AND clause to go with WHERESELECT * FROM invoices WHERE billingcountry = 'United Kingdom' AND (total > 5 OR billingcity = 'London') ORDER BY total DESC- why not throw an OR in too (note the single = not double == for equality)SELECT * FROM invoices WHERE billingaddress LIKE '%lupus%'- wildcard searching (notice the case insensitivity this time)SELECT * FROM invoices WHERE billingaddress LIKE '% ave'- can have just one wildcard tooSELECT * FROM invoices WHERE invoicedate BETWEEN date('2013-09-01') AND date('2013-09-20')- date restrictionsSELECT * FROM invoices WHERE billingcountry IN('Germany', 'Canada') ORDER BY billingcountry- restrict to a listSELECT * FROM invoices WHERE billingcountry IN('Germany', 'Canada') ORDER BY billingcountry, total DESC, invoicedate- we can order by several columns

Again, sometimes its nice to format these on multiple lines like this:

SELECT *

FROM invoices

WHERE

billingcountry IN('Germany', 'Canada', 'United Kingdom')

AND (total > 5 OR billingcity = 'London')

AND customerid = 53

ORDER BY

total DESC,

invoicedate

LIMIT 5, 10

Keep exploring the database, trying out increasingly complex SELECT queries.

6. Primary keys, foreign keys and joining tables

You may have noticed that in db.albums (my way of referring to the albums table in the database) there were fields/columns for both AlbumId and ArtistId. If we run the query SELECT sql FROM sqlite_schema WHERE name='albums' we can see the schema/setup for this table, and these are the key lines:

[AlbumId] INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT NOT NULL,

[ArtistId] INTEGER NOT NULL,

FOREIGN KEY ([ArtistId]) REFERENCES "artists" ([ArtistId])

In db.albums, AlbumId is a PRIMARY KEY and ArtistId is a FOREIGN KEY that references the artists table. All tables should have a primary key, which is unique to each row/record. Look through db.albums and you should see each row has a different number for this field.

But several rows share the same ArtistId. This is a foreign key which references rows in db.artists. Let's use that fact to JOIN the tables together.

SELECT * FROM albums LIMIT 5 - before we join we just have albumid, title and artistid:

┌───┬─────────┬───────────────────────────────────────┬──────────┐

│ │ AlbumId │ Title │ ArtistId │

├───┼─────────┼───────────────────────────────────────┼──────────┤

│ 0 │ 1 │ For Those About To Rock We Salute You │ 1 │

│ 1 │ 2 │ Balls to the Wall │ 2 │

│ 2 │ 3 │ Restless and Wild │ 2 │

│ 3 │ 4 │ Let There Be Rock │ 1 │

│ 4 │ 5 │ Big Ones │ 3 │

└───┴─────────┴───────────────────────────────────────┴──────────┘

SELECT * FROM albums JOIN artists ON albums.artistid = artists.artistid LIMIT 5 - now we have the name field too from db.artists:

┌───┬─────────┬───────────────────────────────────────┬──────────┬───────────┐

│ │ AlbumId │ Title │ ArtistId │ Name │

├───┼─────────┼───────────────────────────────────────┼──────────┼───────────┤

│ 0 │ 1 │ For Those About To Rock We Salute You │ 1 │ AC/DC │

│ 1 │ 2 │ Balls to the Wall │ 2 │ Accept │

│ 2 │ 3 │ Restless and Wild │ 2 │ Accept │

│ 3 │ 4 │ Let There Be Rock │ 1 │ AC/DC │

│ 4 │ 5 │ Big Ones │ 3 │ Aerosmith │

└───┴─────────┴───────────────────────────────────────┴──────────┴───────────┘

It's a bit messy though because the column heading are a bit ambiguous. Let's fix that:

SELECT albumid, title as 'Song name', name as 'Artist'

FROM albums

JOIN artists

ON albums.artistid = artists.artistid

LIMIT 5

┌───┬─────────┬───────────────────────────────────────┬───────────┐

│ │ AlbumId │ Song name │ Artist │

├───┼─────────┼───────────────────────────────────────┼───────────┤

│ 0 │ 1 │ For Those About To Rock We Salute You │ AC/DC │

│ 1 │ 2 │ Balls to the Wall │ Accept │

│ 2 │ 3 │ Restless and Wild │ Accept │

│ 3 │ 4 │ Let There Be Rock │ AC/DC │

│ 4 │ 5 │ Big Ones │ Aerosmith │

└───┴─────────┴───────────────────────────────────────┴───────────┘

We could have achieved the same results this way too:

SELECT albumid, title as 'Song name', name as 'Artist'

FROM albums, artists

WHERE albums.artistid = artists.artistid

LIMIT 5

... and if we have column name clashes or want to use labels, we can do things like this:

SELECT a.albumid, a.title as 'Song name', r.name as 'Artist'

FROM albums as a, artists as r

WHERE a.artistid = r.artistid

LIMIT 5

Of course, we can also add in more WHERE clauses too if we want, with the word AND between them (or OR).

Continue to explore the database, seeking out foreign key relationships that you can join on.

7. User input and SQL injection attacks

Let's make a simple CLI program that alows a user to interactively query the database. We'll call it explorer.js and start with this:

WARNING: keep reading to find out why this code is really really bad!

import { sql } from 'bun'

process.env.DATABASE_URL = `sqlite://tutorial.db`

while (true) {

let input = prompt('Which band/artist would you like to search for?')?.toLowerCase()

if (!input) break

console.table(await sql.unsafe(`SELECT * FROM artists WHERE LOWER(name) = '${input}'`))

}

Notice how we're trying to make our searches case-insensitive by running .toLowerCase() on the user's input, and using the SQL function LOWER(name) too when conducting the search.

BUT... and it really is a very big but indeed. You must never have code like the above. Try running it, then when asked which band to search for enter this aerosmith' OR '1'='1 (the quote marks are important).

So what happened? You'll find it sent back all the artists, not just Aerosmith. This is an example of an SQL injection attack, where you've assumed the user would just give you the name of a band, but has manipulated their input to run a query you didn't consider - the full query your code now runs is:

SELECT * FROM artists WHERE LOWER(name) = 'aerosmith' OR '1'='1'

Imagine if instead it was a user logging in and you were checking their password:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE password = 'irrelevant' OR '1'='1'

... oops! They just managed to log in as any user!

Fortunately, Bun by default provides us with an easy way to avoid SQL injection attacks and makes it really hard to be vulnerable to one. We were doing:

await sql.unsafe(`SELECT * FROM artists WHERE LOWER(name) = '${input}'`)

which has this scary word unsafe in it for a reason! Instead, just make sure you don't use that unsafe() function, and ensure you don't have any quote marks around the user input:

await sql`SELECT * FROM artists WHERE LOWER(name) = ${input}`

You can find out about how Bun uses prepared statements with tagged template literals to protect you from SQL injection. Importantly for you, as long as you're using sql`...` instead of sql.unsafe(...) then you're protected.

Here's our fixed, safe code:

import { sql } from 'bun'

process.env.DATABASE_URL = `sqlite://tutorial.db`

while (true) {

let input = prompt('Which band/artist would you like to search for?')?.toLowerCase()

if (!input) break

console.table(await sql`SELECT * FROM artists WHERE LOWER(name) = ${input}`)

}

To make our program more user-friendly, we may just want to search for a part of a band's name, using % wildcard matching. We can do that like this, though it's a bit fiddly with a nested ${}:

await sql`SELECT * FROM artists WHERE name LIKE ${`%${input}%`}`

... again, because we're using the SQL tagged template literal function correctly, and not using sql.unsafe(), we're protected against SQL injection attacks.

Putting it all together, our SQL injection safe script is now:

import { sql } from 'bun'

process.env.DATABASE_URL = `sqlite://tutorial.db`

while (true) {

let input = prompt('Which band/artist would you like to search for?')?.toLowerCase()

if (!input) break

console.table(await sql`SELECT * FROM artists WHERE name LIKE ${`%${input}%`}`)

}

How can you take this script further? Here are some ideas:

- after finding an artist, if a user enters the

ArtistId, can you show some of their tracks? - could a user search by track name instead?

- use

SELECT name FROM sqlite_schema WHERE type ='table'to list the other tables, andPRAGMA table_info(albums)to see the columns in a table... which other tables could the user search on?

8. The OCR spec

I've covered a lot of SQL on this page, some of which you don't need to know for the OCR A-level. In addition, all I've covered here are SELECT queries - you also need to know about DELETE, INSERT and DROP queries to actually edit a database. Here are the commands you need for the A-level:

SELECTincluding nestedSELECTsSELECT *ie the*whildcard... FROM... WHERE... LIKEwith%wildcards... AND... OR... JOINinner joins; no need for outer, left or right joinsDELETE FROM ...to delete rowsINSERT INTO ...to add rowsDROP TABLE ...to delete a whole table

For exams, you don't need to know how to CREATE ... or UPDATE ... a table or how to add/remove indexes from tables... but it's well worth learning!

9. Guides, further reading and solving mysteries

Pick and choose from these:

- use the interactive W3Schools SQL guide to learn more queries

- the guide at SQLiteTutorial is also good

- ready to solve crime with SQL?

- or solve a whodunnit murder mystery?

- SQL Academy is made by another compsci teacher

- see chapters 18 and 19 in the textbook